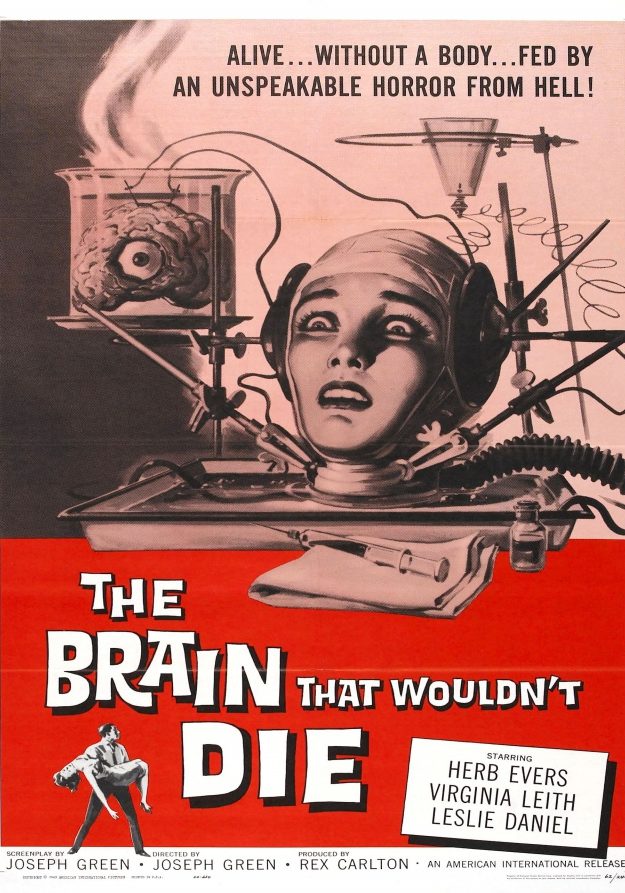

“I can’t let you die; I won’t let you die”: A Grisly Tale of Love and Obsession

In the 1962 black-and-white horror film “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die,” director Joseph Green takes viewers on a chilling journey that pushes the boundaries of science and tests the limits of love. This cinematic oddity presents us with Dr. Bill Cortner, a maverick surgeon who survives a tragic car accident that decapitates his fiancée Jan Compton. Unwilling to let her die, Dr. Cortner preserves her head and embarks on a twisted quest to find a new body for the love of his life. As the title suggests, Jan’s brain refuses to die, setting the stage for a narrative that’s as macabre as it is fascinatingly morbid.

Chilling Visions: Crafting the Horror Atmosphere

The horror of “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die” emerges from an ethereal concoction of suspense and unsettling visuals. Green’s cinematic playground revels in its B-movie status, creating an atmosphere rich with a sense of foreboding that permeates each scene. Through the use of shadowy corridors and an eerie, secluded laboratory, the movie elicits a claustrophobic terror that harks back to the gothic horrors of an older era.

The tension built by the director is palpable. He manipulates viewers’ fear not through explicit gore—though there are certainly some cringe-worthy moments of early practical effects—but through the uncomfortable innuendo of what lurks around the corner. This anticipation of horror is what ultimately gives the film its spine-chilling dynamic.

Cinematic Shadows and Screams

The cinematography of “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die,” while limited by its budget, leverages stark lighting and thoughtful camera angles that evoke a mood appropriate for the unsettling narrative. The monochromatic palette emphasizes the gradient from blinding light to impenetrable darkness, often leaving the viewer anxious about what might emerge from the shadows.

The soundtrack and sound effects, though scarce by modern standards, punctuate key moments with eerie tones. In particular, the silence that accompanies the more grotesque scenes paradoxically amplifies the horror; the lack of sound demands the viewer’s full attention and apprehension.

Acts of Fear and Madness

In a movie so singular in its premise, performances anchor the wild ride. Jason Evers, playing Dr. Cortner, captures the frenzied desperation of a man both brilliant and unhinged. Virginia Leith, as the voice of Jan’s decapitated head, offers an eerily serene yet emotionally nuanced portrayal that oscillates between vulnerability, contempt, and despair.

The characters encounter terror in ways that are at turns believable and melodramatic, which is a staple attribute of the genre during this era. The actors’ responses to the bizarre circumstances drive home the horror through a mix of overwrought emotion and disturbing calm.

Regarding the typology of horror on display, “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die” fits snugly into the realm of body horror, with its focus on the mutilation and modification of the human form, and it challenges conventions by intertwining its grotesque aspects with melodrama and ethical quandaries.

Dissection of the Macabre

The tactics used to frighten the audience are decidedly a mix of psychological horror and shock. The film effectively implements these techniques, though contemporary viewers may find them less shocking than past audiences due to evolving standards in horror cinema. However, the unsettling core of the film and its progression towards the bizarre stays with the viewer.

Under the surface, “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die” touches upon themes of obsession, the ethics of scientific progress, and the nature of consciousness. These underlying currents elevate the film, offering viewers more than just grotesque images; they provide substance for thought and discussion.

As a critic, I find the movie both endearing for its audacity and reflective in its own unique way. Its effectiveness may wane for modern audiences desensitized to graphic content, but it remains a fascinating relic of its time, ripe for those with an appreciation for vintage horror.

Fans of classic horror and those with a taste for B-movies will especially enjoy this film. Its peculiar charm may also allure those looking for a snapshot of the genre’s history and its early explorations of body horror.

While it holds little ground against the polished terrors of contemporary films, its place amongst cult classics is solidified. “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die” is a film that surprises with its depth beneath an ostensibly simple surface.

In conclusion, “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die” is an essential watch for enthusiasts seeking to trace the visceral lineage of horror cinema. For the casual viewer, it may serve as an intriguing, if not a peculiar, glimpse into the genre’s past.

Please note, some viewers might find the themes and visuals disturbing, although they’re tame by today’s standards. Approach this film as a chronological step in horror’s evolution and enjoy the ride—headfirst into terror.